Analysis 28 May 2025

Africa Kenya Political and Country Risk

Although World Bank estimates have placed Kenya’s yearly infrastructure financing gap at around USD 2.1bn for more than ten years, the value of private investments into public-private partnership (PPP) infrastructure projects in Kenya has recently been on a downward trend. PPP financing has declined 91% from 2023, going from USD 353m to USD 33m in 2024, having been even higher in 2022, at USD 624m. The sharp decline since 2023 can largely be attributed to the cancellation in November 2024 of airport and energy transmission PPP contracts with the Indian Adani Group, which were valued at around USD 2.5bn, due to widespread integrity concerns.

More broadly, shifting investment priorities in the Global North – such as the US’s “America First” approach – will likely sustain cuts to infrastructure project funding, especially for social infrastructure. This has already been demonstrated by the US government’s discontinuation of Millenium Change Corporation project funding. This is exacerbated by Kenya’s debt-to-GDP ratio, which has risen from 39% of GDP in 2010 to 72% in 2025, underscoring an increasingly constrained fiscal capacity for the government to finance infrastructure projects.

Against this backdrop, the Kenyan government is increasing its efforts to expand the role of local institutional capital in infrastructure financing. This culminated in January in National Treasury Permanent Secretary Chris Kiptoo forming a committee of experts from the private sector to explore and recommend policies for mobilising long-term capital from local financial markets for infrastructure projects.

A couple of weeks later, the promoters of a USD 3.5bn 440-km expressway project between Nairobi and Mombasa in Kenya, dubbed the USAHIHI project, announced they would raise an unprecedented USD 1bn bond through local pension funds, investment banks, and insurance companies. These developments underline the local currency impetus of both the public and private sector.

Kenya’s need for investment into strategic infrastructure such as roads, energy, and airport infrastructure remains critical to sustain and develop economic activities. For instance, in the energy sector, Kenya is facing the dual challenge of aging transmission infrastructure and increasing pressure on power generation capacity.

Inadequate and aging transmission infrastructure contributes to approximately 23.65% in energy system losses, which are then borne by the consumer through increased energy costs, electricity supply inconsistency, and elevated operational challenges for industrial operators. To remedy transmission issues, the Kenya Transmission Company (KETRACO) has outlined the need to expand the transmission network and estimates that it would require an estimated USD 4.8bn, with a funding gap of USD 3.8bn, highlighting the scale of outstanding capital requirements.

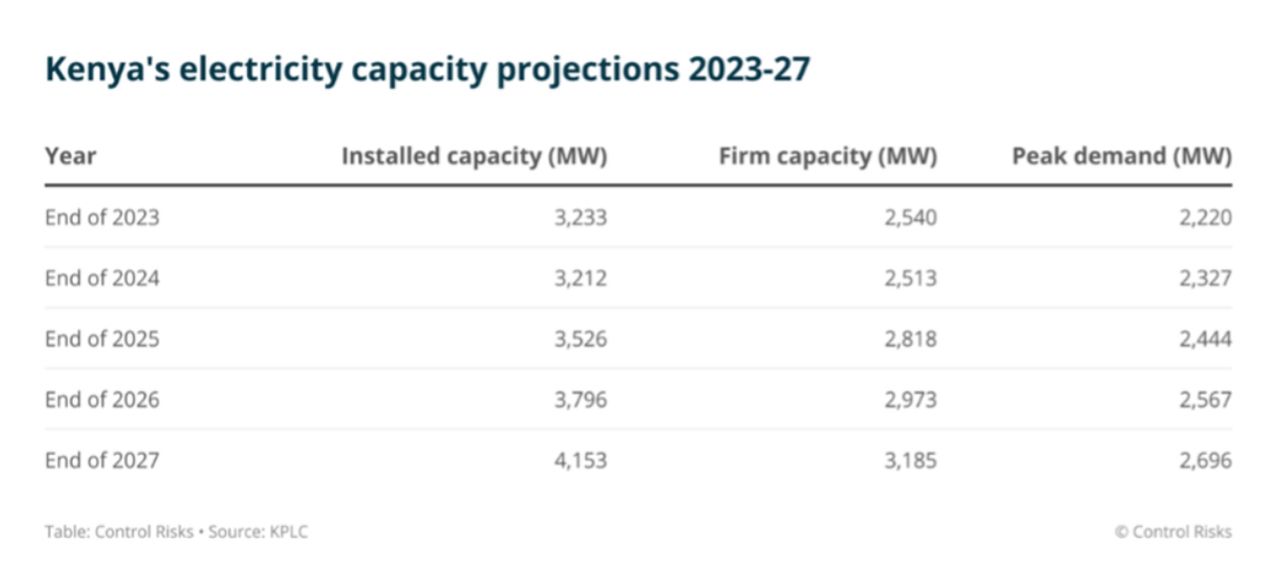

To prevent load-shedding, the Kenya Power and Lighting Company (KPLC) has earmarked projects to onboard an additional 857 MW of firm capacity to maintain stability in the electricity supply. However, this brings into focus the prolonged moratorium on new power purchase agreements (PPAs). The moratorium was imposed in 2018 over high power costs, presumably caused by skewed PPAs that favour power producers over consumers. Since 2018, the moratorium has prevented the onboarding of new generation capacity and the renegotiation of PPAs that will be expiring soon.

If Kenya fails to rectify its PPA dilemma, it is a matter of when – not if – Kenya will begin to implement load-shedding. In South Africa, load-shedding is estimated to have cost the economy USD 26.5bn in 2024, emphasising the need to resolve energy infrastructure deficits in Kenya.

To resolve issues of high energy costs and increased supply risks, the Kenyan legislature has sought solutions modelled on South Africa’s approach to alleviating energy shortfalls through private capital. A November 2024 report by the parliamentary committee on energy acknowledged the need to lift the PPA moratorium and to institute an independent power producer (IPP) procurement programme and IPP office modelled on similar ones in South Africa.

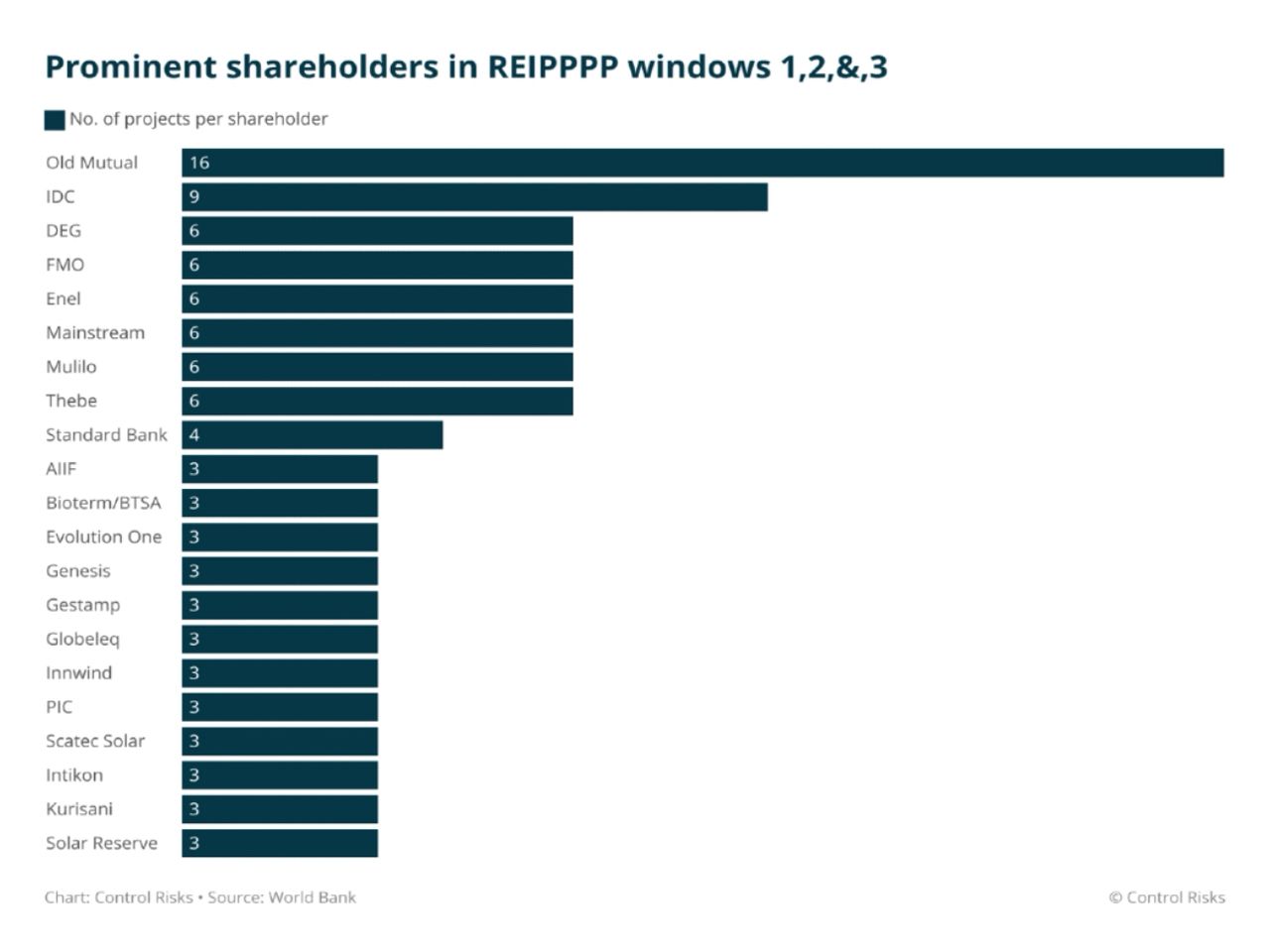

Launched in August 2011, South Africa’s renewable energy power producer programme (REIPPPP) has managed to onboard more than 6,000 MW of renewable energy generation through private-sector investment, despite facing challenges in the more recent past. These challenges stemmed partly from limited political will, which led to bureaucratic delays and the eventual failure of some projects.

South Africa’s part-privatisation of power generation has been championed by domestic capital, with 86% of debt raised within South Africa during the REIPPPP’s first three bid windows. Prominent shareholders include South African financial services institutions, investment corporations, and the Public Investment Corporation, which manages the assets of South Africa’s largest pension fund, the Government Employees’ Pension Fund (GEPF), as illustrated below. The GEPF is also one of the largest investors in the Pan-African Infrastructure Development Fund, a jointly owned fund that invests directly and indirectly in infrastructure.

In Kenya, previous efforts to catalyse pension funds’ involvement have had some success, albeit at a much smaller scale, such as through real estate investment trusts and bonds for road and housing development, totalling USD 113m. Given South Africa has significantly more experience and success crowding in domestic capital, the Kenyan initiative can learn from the challenges they have faced and draw on their successes.

© Black Raptor Ops Group Holdings Ltd registration no.01548306